The Application Code Reviewer (ACR) is a tool built for developers to help with code review. It scans a Mendix project and detects bugs, performance issues, security vulnerabilities and more. ACR does this by comparing a Mendix project against a database of development rules based on Mendix best practices and community guidelines. To learn more see the live demo recording.

Whenever I talk about the ability of ACR to detect bugs, I am greeted with a large dose of skepticism. For example, I often hear people saying:

"How can you know if something is a bug without understanding the business case i.e. how functionality is supposed to work?"

This makes a lot of sense. By definition, a bug is some behavior that does not fit the requirements of the program. But there are some behaviors, for example, program crashes, that are certainly not part of any requirements. At a lower level, logical errors in algorithms are another form of bugs that are not related to requirements. Without going into a theoretical discussion let's examine what actually leads to bugs in the real world.

The making of a bug

As a developer, I am comfortable saying that developers think very highly of them(our)selves. We take pride in what we do and think we are very good at it. Therefore, we have this idea that if by some miracle a bug comes up it must be in a very complicated piece of code. However, studies show that the origins of most bugs are much more humble.

One of the main sources of bugs turns out to be ... wait for it ... copy-pasting code. This introduces bugs in for example when a piece of code is copied with the intention to modify it slightly at another place. Due to a distraction or for some other reason the modification (or part thereof) is not done. For more examples, I recommend this brilliant post about The Last Line Effect.

Another big source of bugs is over-confidence and the corresponding lack of attention. In this scenario, a developer is implementing some trivial algorithm that gives a sense of "This is so easy, I've done it many times before" which leads to silly errors. Check out some real examples here.

As you can see, none of the above sources of bugs have much to do with business logic. And while these bugs might be difficult for a human to spot they are fairly easy to spot by a machine.

In the next part of this blog post, I will share some example of Mendix microflows and expressions that contains errors. These buggy examples are from real Mendix projects that I have worked on (with minor simplification to make them more illustrative).

To make it more fun I encourage you to find the error yourself before checking the answer.

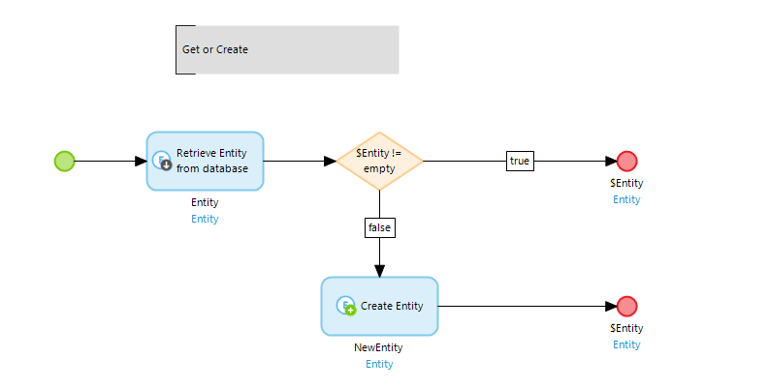

Exhibit A: Get or create

Ah, my favorite. Whenever lazy loading is needed this is the preferred approach. Check if an object exists in the database and if not create it. Since it is not possible to reassign object variables in Mendix I often use a separate microflow for this. So easy, so trivial. Its only 3 actions, what could possibly go wrong? Can you spot the error?

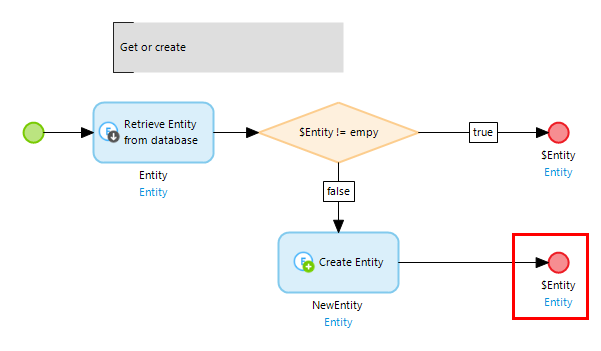

It turns out that the newly created entity is not returned. It is a mistake that is easy to make. Luckily, ACR has several rules that will trigger a violation in this case. For one, the variable

$Entity is definitely

empty in the

false flow which violates

the rule that empty should not be implicitly returned or assigned. Secondly, this microflow has multiple end events all of which return the same value which is also a

violation. Finally, the variable

NewEntity is not used which is a violates the

rule that declared variables should be used.

It turns out that the newly created entity is not returned. It is a mistake that is easy to make. Luckily, ACR has several rules that will trigger a violation in this case. For one, the variable

$Entity is definitely

empty in the

false flow which violates

the rule that empty should not be implicitly returned or assigned. Secondly, this microflow has multiple end events all of which return the same value which is also a

violation. Finally, the variable

NewEntity is not used which is a violates the

rule that declared variables should be used.

Exhibit B: The missing switch case

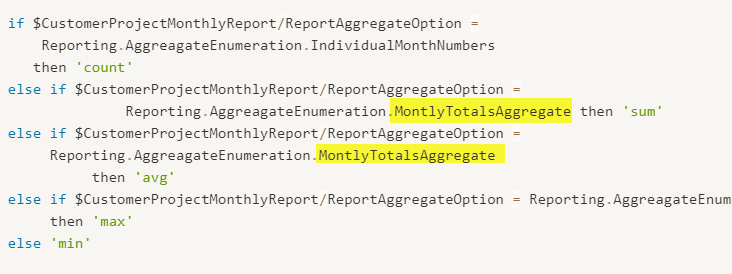

Due to a lack of switch case in Mendix expressions, I often write chains of if-else if statements. See if you can spot the error in the following expression.

| if $CustomerProjectMonthlyReport/ReportAggregateOption = |

The answer:

This is a great example of a copy-paste bug. Long variable names that no-one wants to type coupled with a repeating pattern. Again with ACR, it is very easy to find any such and similar mistakes.

Exhibit C: Make empty string comparison great again

Every Mendix developer knows that a check for empty string needs to check for both an empty string value i.e. '' and an empty i.e. null variable/member. This is often combined with a trim to require meaningful user input. This is something that every developer does probably several times a day. So there should be no errors in the following expression (1):

trim($Str) != ''and $Str != empty

or this one (2):

$SignupHelper/AddressCityCode != empty and trim($SignupHelper/AddressCountryCode) != ''

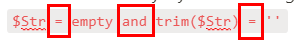

If that was too easy, try the following one (3):

$Str = empty and trim($Str) = ''

The answers:

(1) the trim is done before checking if the variable is empty . If the variable is indeed empty the check for empty will not even be triggered because the trim will fail with a null pointer exception 😱.

(2) A different variable is compared for empty than the one that is being trimmed. Although this is technically correct code and will not cause any errors it is very likely not what the developer intended.

(3) When comparing for empty there are three operators to write, each with two options:

This leads to 8 possible combinations of which only two are correct: if $A != empty and trim($A) != '' then $A else 'empty' , and if $A = empty or trim($A) = '' then 'empty' else $A .

All other combinations are wrong.

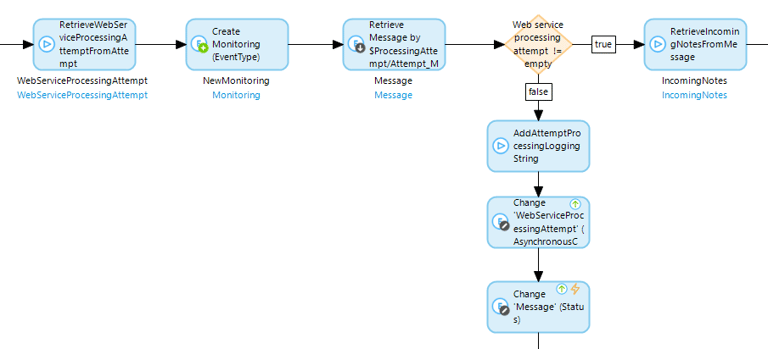

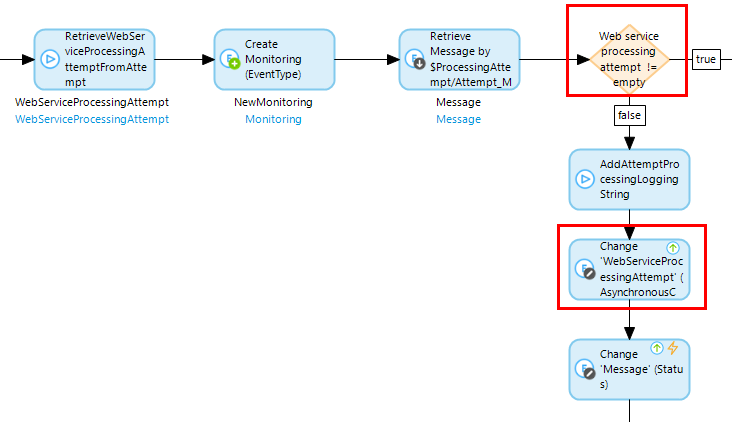

Exhibit D: The dreaded null pointer exception

According to the java docs, a null pointer exception is thrown when an application attempts to use an empty value in a cases where a value is required. With that hint can you spot the error in the following microflow?

The reason why

this rule is considered critical in ACR is because there is not even a chance that this flow does what is intended. At the first occurrence of an

empty object, the

false flow will lead straight to a null pointer exception and a nasty error for the user and perhaps

corrupted data in the database.

The reason why

this rule is considered critical in ACR is because there is not even a chance that this flow does what is intended. At the first occurrence of an

empty object, the

false flow will lead straight to a null pointer exception and a nasty error for the user and perhaps

corrupted data in the database.

To briefly summarize every developer makes mistakes while developing. That much is clear. With this post, I hope to have convinced you that many of these mistakes can indeed be detected by a machine without any knowledge of the business case for the app that is being reviewed.

The automatic code reviewer for Mendix checks for over 100 rules in different categories such as security, performance, and maintainability. There are also 30 reliability rules whose goal is to find bugs in your app. These rules check for example that:

- Return expressions for a flow should be different (Exhibit A)

- Chain of “if/else if” statements should have different conditions (Exhibit B)

- Check for empty string should be done properly (Exhibit C)

- Empty variables should not be used in actions that throw null pointer exception (Exhibit D)

Not convinced

Sign up for a free trial and experience the power of automated code reviews first hand.